________________

MARCH, 1898.]

CURRENCY AND COINAGE AMONG THE BURMESE.

3.

The above tables shew that, in terms of the rati, 33 tola 1 pala, which is what the modern South Indian average scale states to be approximately the case. We have then here, as it seems to me, a reasonable explanation of the descent of the modern Muhammadan South Indian scale from that of North India, and from the tables already given in this Section it can be seen that the main points of the Muhammadan and Hindu scales of South India are identical at candy, maund, viss and pollum (to use the Anglo-Indian forms). One can then also say that the whole modern South Indian scale is related to the North Indian through the scale of rati, tola and ser, rather than through the scale of raktika, masha and pala.

I think one can hardly doubt that there were for centuries two separate concurrent scales in North India, pretty much as I gather was also formerly the case in China, i. e.. the recognised or literary and the popularThus, after giving a long series of scales from all sorts of books, working out generally to the scale of rakkika, masha and pala (820 raktikas to the pala) Colebrooke, Essays, Vol. II. p. 531, states significantly: "To these I do not add the masha of 8 rakitkás, because it has been explained as (being) meastired by eight silver ratti weights, each twice as heavy as the seed. Yet as a practical denomination it must be noticed. Eight such rattis make one masha, but twelve elve mdalas compose one tola. This tola is nowhere suggested by the Hindu legislators." That is, the seale of rats, tola and sér (96 ratis to the tola) is not the old literary recognised scale, yet it is unquestionably the scale that the Muhammadan conquerors picked up, and is essentially that adopted by South India and modern India generally. One may safely argue that the Muhammadan conquerors would in the ordinary course of things be more likely to pick up and adopt a popular scale, than an orthodox and literary one, for their weights and measures, and I apprehend that this is what they did.+3 Hence my designation of the scale of 320 raktikas to the pala as the literary scale and of the scale of 96 ratis to the tôla as the popular scale, at any rate in the XVth and XVIth Centuries A. D., whence the modern coinages date.

With regard to the popular scale Colebrooke states, p. 536:-"The Vṛihat-rájamartanda specifies measures which do not appear to have been noticed in other Sanskrit writings:

24 tôlakas 1 sêr (? sêtaka)

2 sêrs = 1 prabh (? prabhu)

It is mentioned in the Ayin-i-Akbari that the ser formerly contained 18 dûms in some parts of Hindustan and 22 in others, but that it consisted of 28 at the cominencement of the reign of Akbar, and was fixed at 5 tanks or 20 máshas, or, as stated in one place, 20 mashas 7 rattis. The ancient sér noticed in the Ayin-i-Akbari therefore coincided nearly with the sér stated in the Rajamartanda. The double sér is still (1799) used in some places, but called by the same name (panche-séri)44 as the weight of five sers employed in others."

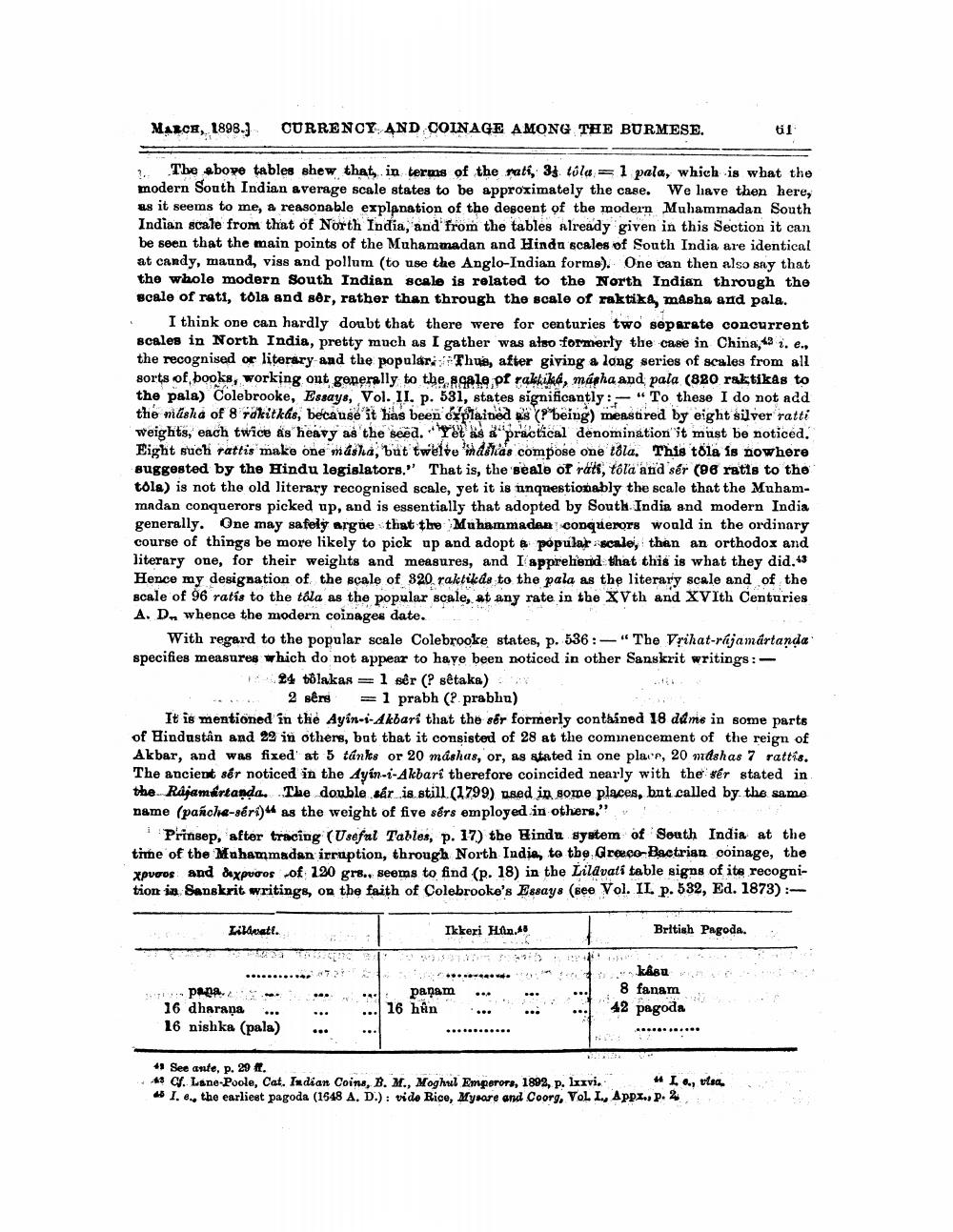

Prinsep, after tracing (Useful Tables, p. 17) the Hindu system of South India at the time of the Muhammadan irruption, through North India, to the Greece Bactrian coinage, the Xpueros and expooros of 120 grs., seems to find (p. 18) in the Lilavati table signs of its recognition in Sanskrit writings, on the faith of Colebrooke's Essays (see Vol. II. p. 532, Ed. 1873):--

British Pagoda.

Lilavati.

s pana 16 dharana

16 nishka (pala)

RiseEnc

til

Ikkeri Hûn.48

panam 16 hân

...kâsu 8 fanam 42 pagoda

41 See ante, p. 29.

43 Cf. Lane-Poole, Cat. Indian Coins, B. M., Moghul Emperors, 1892, p. lxxvi.

44 L. o., visa,

45 I. e., the earliest pagoda (1648 A. D.): vide Rice, Mysore and Coorg, Vol. I., App., p. 2