________________

156

THE INDIAN ANTIQUARY.

[JUNE, 1896.

I have grouped together conjointly point to a probability of his having lived a considerable time, say three or four centuries, before the Chôla king and poet, Kauḍarâditya. But there are one or two other considerations to enforce the same conclusion, and I shall now proceed to explain them.

Let us, for example, inquire whether Sanskrit literature can throw any light on the subject, corroborating our position or otherwise. From the summary inquiry we held in a previous part of this paper, we found reasons for believing that Sambandha preceded, not only Ramanuja and Madhvacharya, but Samkara also, the greatest of modern Hindû philosophers. Now the age of Samkaracharya is diversely estimated. The Hon'ble Mr. Telang1 adduces certain sound reasons for placing Samkara in the sixth century, while Dr. Fleet has equally cogent reasons for believing that he lived about 630-655 A. D. The latest date yet assigned to this philosopher, as, for instance, by Mr. Pathak, is the eighth century. We have then in Samkara an Indian celebrity who lived about two or three centuries before Kandarâditya, or much about the time to which we have been able to trace Sambandha by means of purely literary records in Tamil. The history of the religious development in Southern India, pointing as it does in the same direction, raises a strong antecedent probability in favour of finding Sambandha somewhere about the time of, or immediately before, 'Samkara.

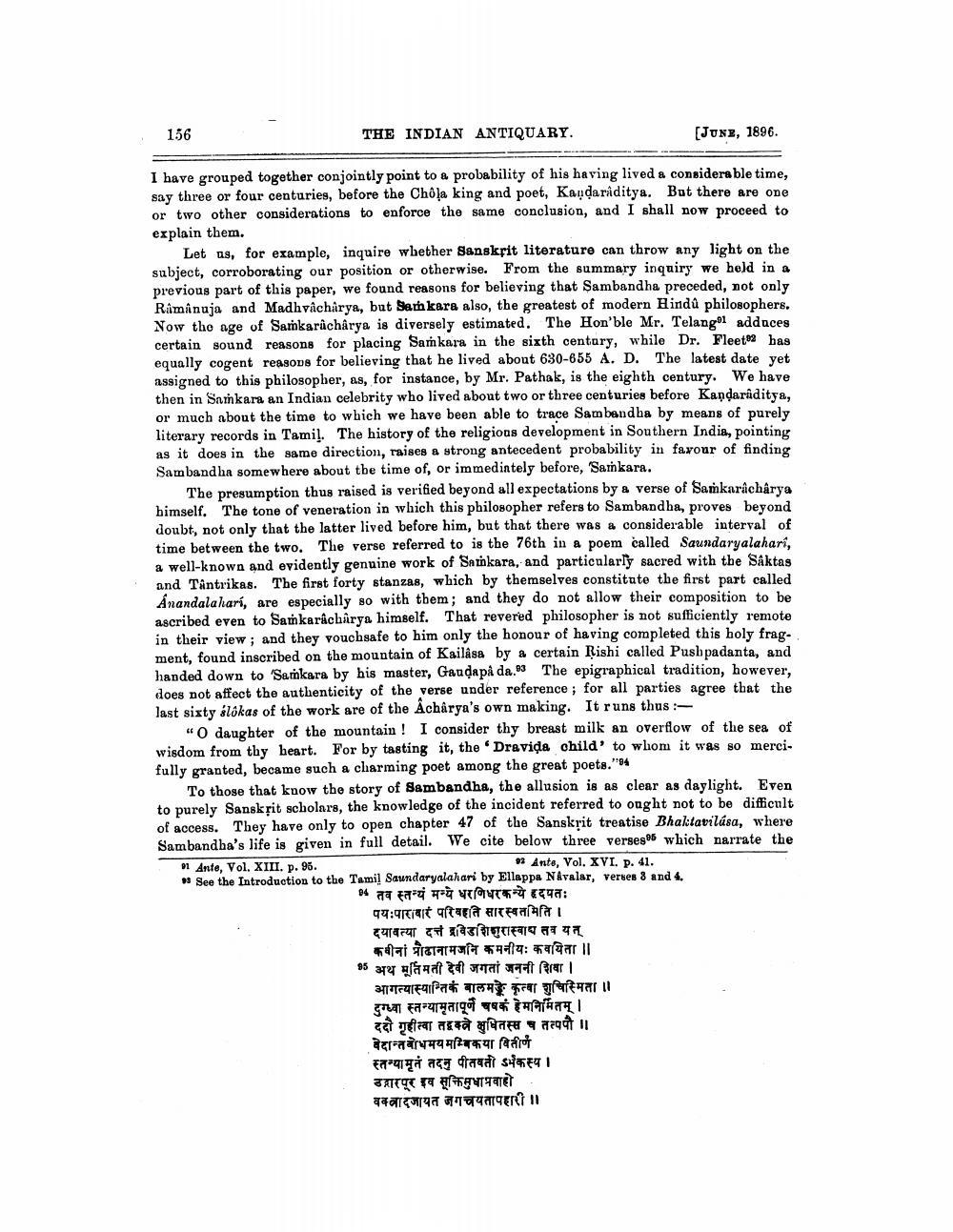

The presumption thus raised is verified beyond all expectations by a verse of Samkaracharya himself. The tone of veneration in which this philosopher refers to Sambandha, proves beyond doubt, not only that the latter lived before him, but that there was a considerable interval of time between the two. The verse referred to is the 76th in a poem called Saundaryalahari, a well-known and evidently genuine work of Sankara, and particularly sacred with the Sâktas and Tantrikas. The first forty stanzas, which by themselves constitute the first part called Anandalahari, are especially so with them; and they do not allow their composition to be ascribed even to Samkaracharya himself. That revered philosopher is not sufficiently remote in their view; and they vouchsafe to him only the honour of having completed this holy fragment, found inscribed on the mountain of Kailasa by a certain Rishi called Pushpadanta, and handed down to 'Samkara by his master, Gauḍapå da.93 The epigraphical tradition, however, does not affect the authenticity of the verse under reference; for all parties agree that the last sixty slokas of the work are of the Acharya's own making. It runs thus:

"O daughter of the mountain! I consider thy breast milk an overflow of the sea of wisdom from thy heart. For by tasting it, the 'Dravida child' to whom it was so mercifully granted, became such a charming poet among the great poets."94

To those that know the story of Sambandha, the allusion is as clear as daylight. Even to purely Sanskrit scholars, the knowledge of the incident referred to ought not to be difficult of access. They have only to open chapter 47 of the Sanskrit treatise Bhaktavilása, where Sambandha's life is given in full detail. We cite below three verses which narrate the 92 Ante, Vol. XVI. p. 41.

91 Ante, Vol. XIII. p. 95.

See the Introduction to the Tamil Saundaryalahari by Ellappa Navalar, verses 3 and 4.

94 तव स्तन्यं मन्ये धरणिधरकन्ये हृदपतः पयः पारावारं परिवहति सारस्वतमिति । दयावत्या दत्तं द्रविडशिशुरास्वाद्य तव यत् कवीनां प्रौढानामजनि कमनीयः कवयिता ॥ 95 अथ मूर्तिमती देवी जगतां जननी शिक्षा | आगत्यास्यान्तिकं बालमङ्के कृत्वा शुचिस्मिता ॥ दुग्ध्वा स्तन्यामृतापूर्णे चषकं हेमनिर्मितम् | दीगृहात वेदान्तबोधमय मम्बिकया वितीर्ण स्तन्यामृतं तदनु पीतवती कस्य । उगारपूर इव सूक्तिमुधाप्रवाहो वक्त्रादजायत जगचयतापहारी ॥

॥