________________

SEPTEMBER, 1890.)

BOOK-NOTICES.

287

hata kachhu sújha na Ord should be metrically divided thus:

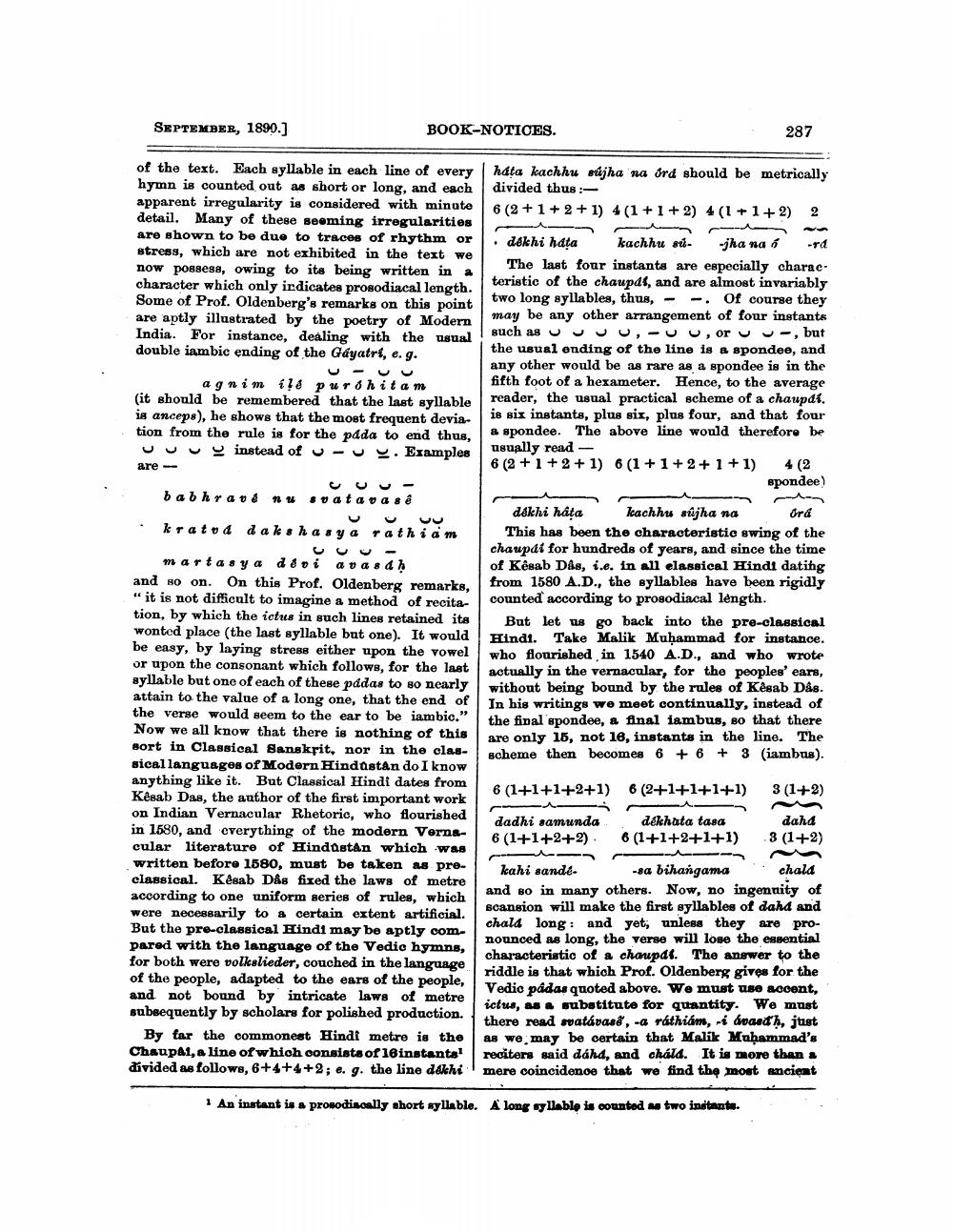

(9 + 1 + 2 + 11441 +1 +2 4 (1+119)

of the text. Each syllable in each line of every hymn is counted out as short or long, and each apparent irregularity is considered with minute detail. Many of these seeming irregularities are shown to be due to traces of rhythm or stress, which are not exhibited in the text we now possess, owing to its being written in a character which only irdicates prosodiacal length. Some of Prof. Oldenberg's remarks on this point are aptly illustrated by the poetry of Modern India. For instance, dealing with the usual double iambic ending of the Gayatri, e.g.

• dekhi hata kachhu sú- -jha na 6 rd

The last four instants are especially characteristic of the chaupal, and are almost invariably two long syllables, thus, - -. Of course they may be any other arrangement of four instants such as Uuuu,-uu, oruu-, but the usual ending of the line is a spondee, and any other would be as rare as a spondee is in the fifth foot of a hexameter. Hence, to the average reader, the usual practical scheme of a chaupdí. is six instants, plus six, plus four, and that four a spondee. The above line would therefore be usually read 6 (2 + 1 + 2 +1) 6 (1 + 1 + 2 + 1 +1) 4 (2

spondee)

agnim il & purohitam (it should be remembered that the last syllable is anceps), he shows that the most frequent devia. tion from the rule is for the pada to end thus, uuuy instead of u-uy. Examples are -

babhrau a nu satava se

• kratua daksha syarathi am

dekhi hata kachhu sújha na Ora

This has been the characteristio swing of the chaupai for hundreds of years, and since the time of Kesab Dås, i.e. in all elassical Hindi dating from 1580 A.D., the syllables have been rigidly counted according to prosodiacal length.

But let us go back into the pre-classical Hindt. Take Malik Muḥammad for instance. who flourished in 1540 A.D., and who wrote actually in the vernacular, for the peoples' ears, without being bound by the rules of Kesab Dås. In his writings we meet continually, instead of the final spondee, a final iambus, so that there are only 15, not 18, instants in the line. The scheme then becomes 6 + 6 + 3 (iambus).

6 (1+1+1+2+1)

6 (2+1+1+1+1)

3 (1+2)

martas y a deui avas dh and so on. On this Prof. Oldenberg remarks, " it is not difficult to imagine a method of recitation, by which the ictus in such lines retained its wonted place (the last syllable but one). It would be easy, by laying stress either upon the vowel or upon the consonant which follows, for the last gyllable but one of each of these padas to so nearly attain to the value of a long one, that the end of the verse would seem to the ear to be iambio." Now we all know that there is nothing of this sort in Classical Sanskrit, nor in the classical languages of Modern HindastAn do I know anything like it. But Classical Hindt dates from Kesab Das, the author of the first important work on Indian Vernacular Rhetoric, who flourished in 1580, and everything of the modern Vernscular literature of Hindustan which was written before 1580, must be taken as preclassical. Késab Das fixed the laws of metre according to one uniform series of rules, which were necessarily to a certain extent artificial. But the pre-classical Hindi may be aptly compared with the language of the Vedic hymns, for both were volkslieder, couched in the language of the people, adapted to the ears of the people, and not bound by intricate laws of metre subsequently by scholars for polished production.

By far the commonest Hindi metre is the Chaupai, a line of which consists of 16 instanta! divided as follows, 6+4+4+2; e. g. the line dakhi

dadhi samunda d ékhata tasa daha 6 (1+1+2+2) 6 (1+1+2+1+1) 3 (1+2) - -

- kahi sande. -sa bihangama chala and so in many others. Now, no ingenuity of scansion will make the first syllables of daha and chald long and yet, unless they are pronounced as long, the verse will lose the essential characteristic of a chapat. The answer to the riddle is that which Prof. Oldenberg gives for the Vedio padas quoted above. We must use accent, ictue, as a substitute for quantity. We must there read watávast", -a ráthiám, - ápasth, just as we may be certain that Malik Muhammad's reciters said dáhd, and cháld. It is more than mere coincidenoe that we find the most ancient

1 An instant is a prosodiacally short syllable. A long syllable is counted

two instanta.