________________

SKETCH OF SABEAN GRAMMAR.

FEBRUARY, 1875.]

2), 'On the day of Yta'el the just, and of his son the saviour, kings of Ma'in.'

The Sabean texts are never dated according to the year of a king. There are two different ways of fixing dates. The first and more, recent relates to a previous time which had, in consequence of some memorable event, become the commencement of a new era. Hitherto only two inscriptions bearing traces of an era are known; namely, the third inscription of Halévy's collection, occurring also in Fresnel under the same number, and the inscription of Hisn G'hurâb. The first bears the phrase 11 DAND DOM 12..., 573 Hayw.' The opinion of Fresnel that the word " means 'may you live,' and was merely added that the phrase should not terminate with the word 'hundred,' which resembles the word mo 'to die,' is too fantastic to be tenable; the only thing certain is that w, written also DT, is a very frequent Sabaan name, and appears here to be that of the engraver. The beginning of this era may be approximatively fixed about 115 years before Christ. This date results from the inscription of Hisn G'hurâb, which is of the year 640 (anti bo on ww), and is the work of a prince escaped from the Ethiopians after their victory over the last Hemyarite king (see 2. d. D. M. G. XXVI. p. 436, the translation by Levy of this inscription). As, however, this last-mentioned event, according to the best chronologies, took place A.D. 525, it is clear that the era in question cannot be of later origin than 115 years before Christ. At that time the Sabæan empire was still in its power. A century afterwards the rumour of the great riches accumulated by the Sabeans had spread as far as Rome, and made such an impression as to tempt the cupidity of Augustus.

The Sabeans, like the Assyrio-Babylonians, instead of fixing dates by an era of long duration, generally preferred to determine them by the use of eponyms; the years were accordingly named after certain celebrated personages, probably kings and governors. It may be seen that in order to designate years the Sabeans used the same system as for indicating remarkable days. Our historical knowledge is so imperfect that these kinds of dates are closed letters to us; but it is possible that when the great ruins in Yemen are excavated, eponymic tablets, like those of the Assyrians, may be dis

41

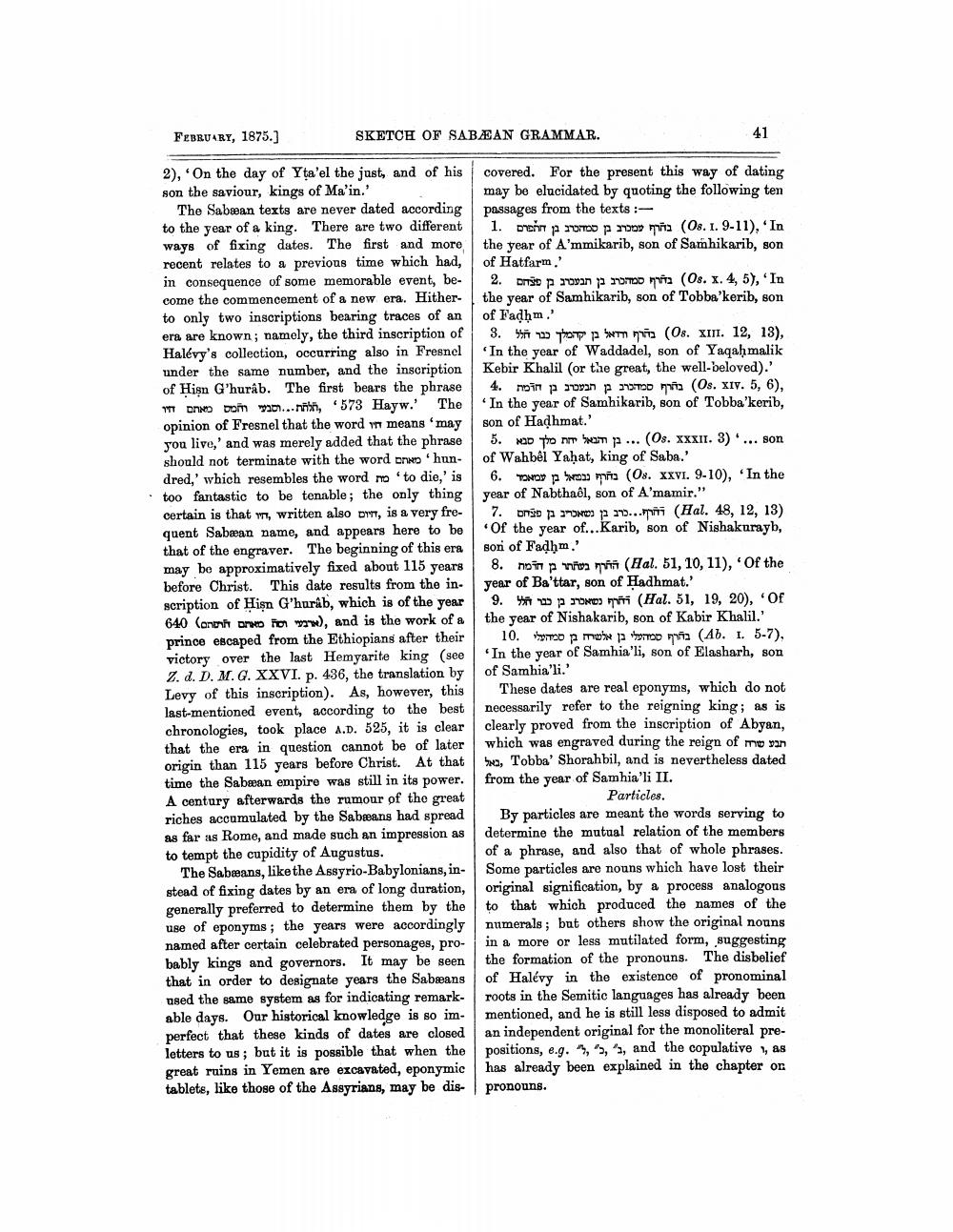

covered. For the present this way of dating may be elucidated by quoting the following ten passages from the texts :

Os. 1. 9-11), In) בחרף עמכון בן סמברג בן התפרם .1

the year of A'mmikarib, son of Samhikarib, son of Hatfarm.'

0s. x. 4, 5, In) בדרך סמהכרב בן תבעברג בן פנחם .2

the year of Samhikarib, son of Tobba'kerib, son of Fadḥm.'

,(13 ,12 .XIII .) בהרף ורדאל בן יקהמלך כבר חלל .3

In the year of Waddadel, son of Yaqahmalik Kebir Khalil (or the great, the well-beloved).'

,(6 ,5 .Os. XIV) בחרף סמהכרב בן הבעברב בן חומות .4

In the year of Samhikarib, son of Tobba'kerib, son of Hadhmat.'

,* (3 .XXXII .... בן והבאל יחת מלך סבא .5

... son

of Wahbel Yaḥat, king of Saba.'

6.

(08. XXVI. 9-10), 'In the year of Nabthaôl, son of A'mamir."

(13 ,12 ,48 .Hal) וחרף...כרב בן נשאכריב בן פנחס .7

Of the year of...Karib, son of Nishakurayb, son of Fadhm.'

(Hal. 51, 10, 11), 'Of the year of Ba'ttar, son of Hadhmat.'

8.

Hal. 119, 20), Of) וחרף נשאכרב בן כבר החלל .9

the year of Nishakarib, son of Kabir Khalil.'

,(5-7 ,I .(4) בהרף סמהעלי בן אלשרה בן סמהכלי .10

'In the year of Samhia'li, son of Elasharh, son of Samhia'li.'

These dates are real eponyms, which do not necessarily refer to the reigning king; as is clearly proved from the inscription of Abyan, which was engraved during the reign of me van 5, Tobba' Shorahbil, and is nevertheless dated from the year of Samhia'li II.

Particles.

By particles are meant the words serving to determine the mutual relation of the members of a phrase, and also that of whole phrases. Some particles are nouns which have lost their original signification, by a process analogous to that which produced the names of the numerals; but others show the original nouns in a more or less mutilated form, suggesting the formation of the pronouns. The disbelief of Halévy in the existence of pronominal roots in the Semitic languages has already been mentioned, and he is still less disposed to admit an independent original for the monoliteral prepositions, e.g. ",", ", and the copulative 1, as has already been explained in the chapter on

pronouns.