________________

THE CANONICAL NIKSEPA

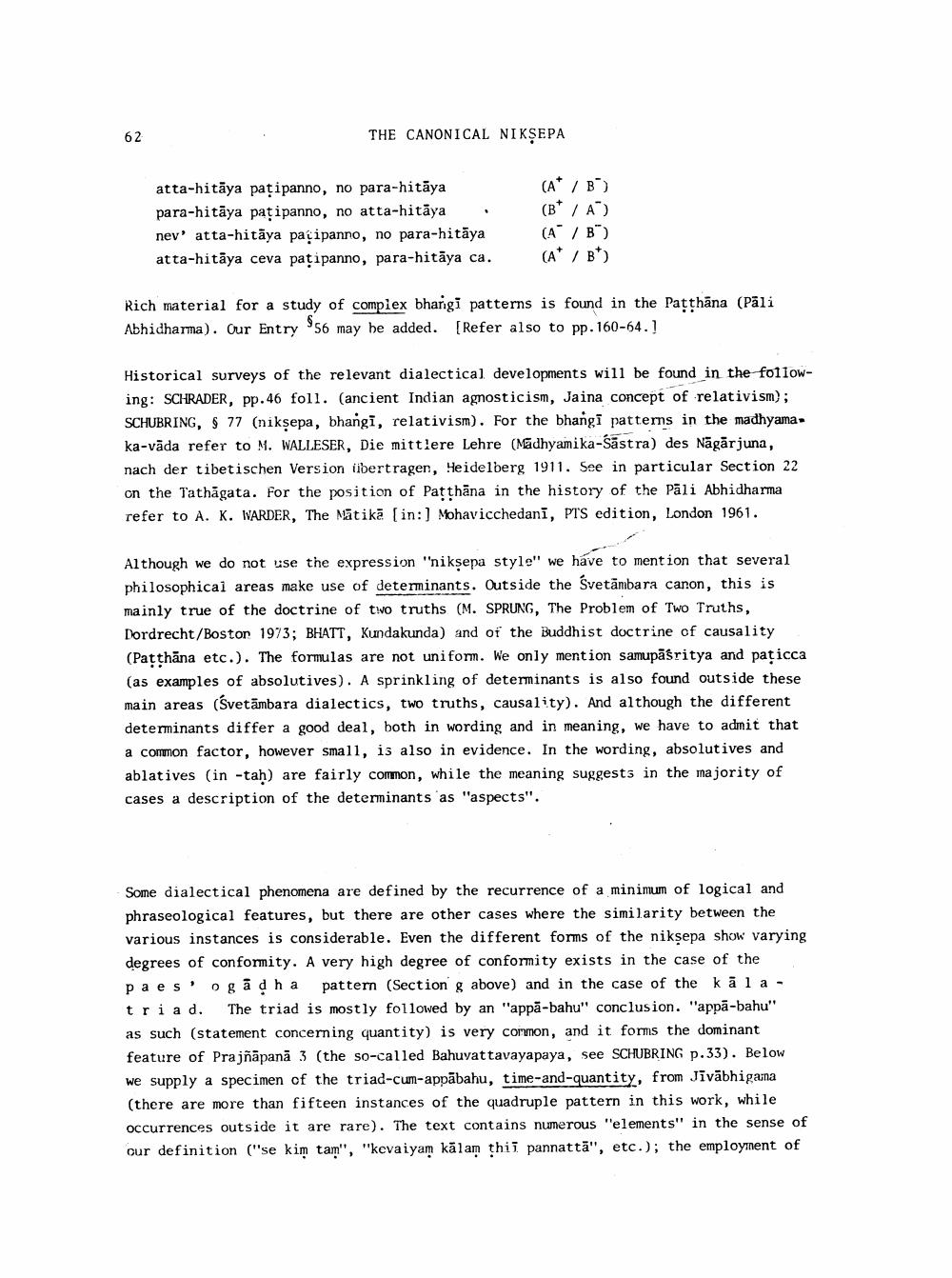

atta-hitāya pațipanno, no para-hitāya para-hitāya patipanno, no atta-hitāya nevatta-hitāya paçipanno, no para-hitāya atta-hitāya ceva pațipanno, para-hitāya ca.

(A / B) (B* A) (A /B) (A* / B)

Rich material for a study of complex bharigi patterns is found in the Patthāna (Pāli Abhidharma). Our Entry #56 may be added. (Refer also to pp. 160-64. !

Historical surveys of the relevant dialectical developments will be found in the following: SCHRADER, pp.46 foll. (ancient Indian agnosticism, Jaina concept of relativism); SCHUBRING, $ 77 (niksepa, bhangi, relativism). For the bhangi patterns in the madhyamaka-vāda refer to M. WALLESER, Die mittlere Lehre (Madhyamika-Šāstra) des Nāgārjuna, nach der tibetischen Version libertragen, Heidelberg 1911. See in particular Section 22 on the Tathāgata. For the position of Patthāna in the history of the Pāli Abhidharma refer to A. K. WARDER, The Mātikā (in:) Mohavicchedani, PTS edition, London 1961.

Although we do not use the expression "nikṣepa style" we have to mention that several philosophical areas make use of determinants. Outside the Svetāmbara canon, this is mainly true of the doctrine of two truths (M. SPRUNG, The Problem of Two Truths, Dordrecht/Boston 1973; BHATT, Kundakunda) and of the Buddhist doctrine of causality (Patthāna etc.). The formulas are not uniform. We only mention samupāśritya and pațicca (as examples of absolutives). A sprinkling of determinants is also found outside these main areas (svetāmbara dialectics, two truths, causality). And although the different determinants differ a good deal, both in wording and in meaning, we have to admit that a common factor, however small, is also in evidence. In the wording, absolutives and ablatives (in-tah) are fairly common, while the meaning suggests in the majority of cases a description of the determinants as "aspects".

Some dialectical phenomena are defined by the recurrence of a minimum of logical and phraseological features, but there are other cases where the similarity between the various instances is considerable. Even the different forms of the nikṣepa show varying degrees of conformity. A very high degree of conformity exists in the case of the paes' ogadha pattern (Section g above) and in the case of the kala - triad. The triad is mostly followed by an "appā-bahu" conclusion. "appā-bahu" as such (statement concerning quantity) is very common, and it forms the dominant feature of Prajñāpanā 3 (the so-called Bahuvat tavayapaya, see SCHUBRING p.33). Below we supply a specimen of the triad-cum-appābahu, time-and-quantity, from Jīvābhigarna (there are more than fifteen instances of the quadruple pattern in this work, while occurrences outside it are rare). The text contains numerous "elements" in the sense of our definition ("se kim tam", "kevaiyam kālam thiī pannattā", etc.); the employment of