________________

Shri Mahavir Jain Aradhana Kendra

www.kobatirth.org

Acharya Shri Kailassagarsuri Gyanmandir

302

OLD BRAHMI INSCRIPTIONS

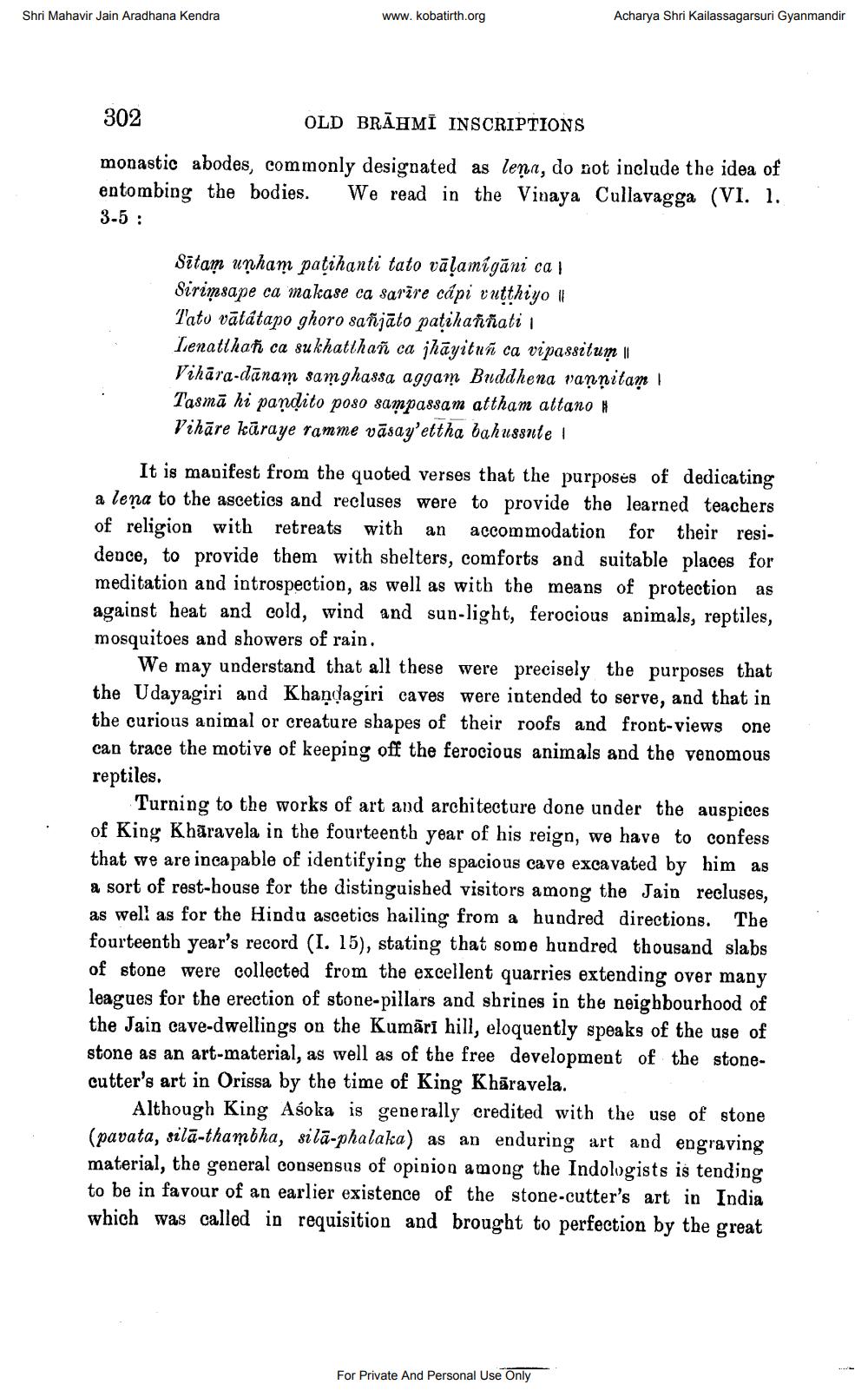

monastic abodes, commonly designated as lena, do not include the idea of entombing the bodies. We read in the Vinaya Cullavagga (VI. 1. 3-5 :

Sitam unham patihanti tato vāļamígāni ca Sirimsape ca makase ca sarire cápi vutthiyo il Tato vātátapo ghoro saħjāto patihanñati i Lenatthañ ca sukhatthañ ca jhāyitun ca vipassitum || Vihara-dānam samghassa aggam Buddhena vannitam! Tasmā hi pandito poso sampassam attham attano # Vihāre kūraye ramme vāsay'ettha bahussute !

It is manifest from the quoted verses that the purposes of dedicating a lena to the ascetics and recluses were to provide the learned teachers of religion with retreats with an accommodation for their residence, to provide them with shelters, comforts and suitable places for meditation and introspection, as well as with the means of protection as against heat and cold, wind and sun-light, ferocious animals, reptiles, mosquitoes and showers of rain.

We may understand that all these were precisely the purposes that the Udayagiri and Khandagiri caves were intended to serve, and that in the curious animal or creature shapes of their roofs and front views one can trace the motive of keeping off the ferocious animals and the venomous reptiles.

Turning to the works of art and architecture done under the auspices of King Khāravela in the fourteenth year of his reign, we have to confess that we are incapable of identifying the spacious cave excavated by him as a sort of rest-house for the distinguished visitors among the Jain recluses, as well as for the Hindu ascetics hailing from a hundred directions. The fourteenth year's record (I. 15), stating that some hundred thousand slabs of stone were collected from the excellent quarries extending over many leagues for the erection of stone-pillars and shrines in the neighbourhood of the Jain cave-dwellings on the Kumāri hill, eloquently speaks of the use of stone as an art-material, as well as of the free development of the stonecutter's art in Orissa by the time of King Khāravela.

Although King Asoka is generally credited with the use of stone (pavata, selā-thambha, silā-phalaka) as an enduring art and engraving material, the general consensus of opinion among the Indologists is tending to be in favour of an earlier existence of the stone-cutter's art in India which was called in requisition and brought to perfection by the great

For Private And Personal Use Only