________________

Chapter 05

Geological Studies

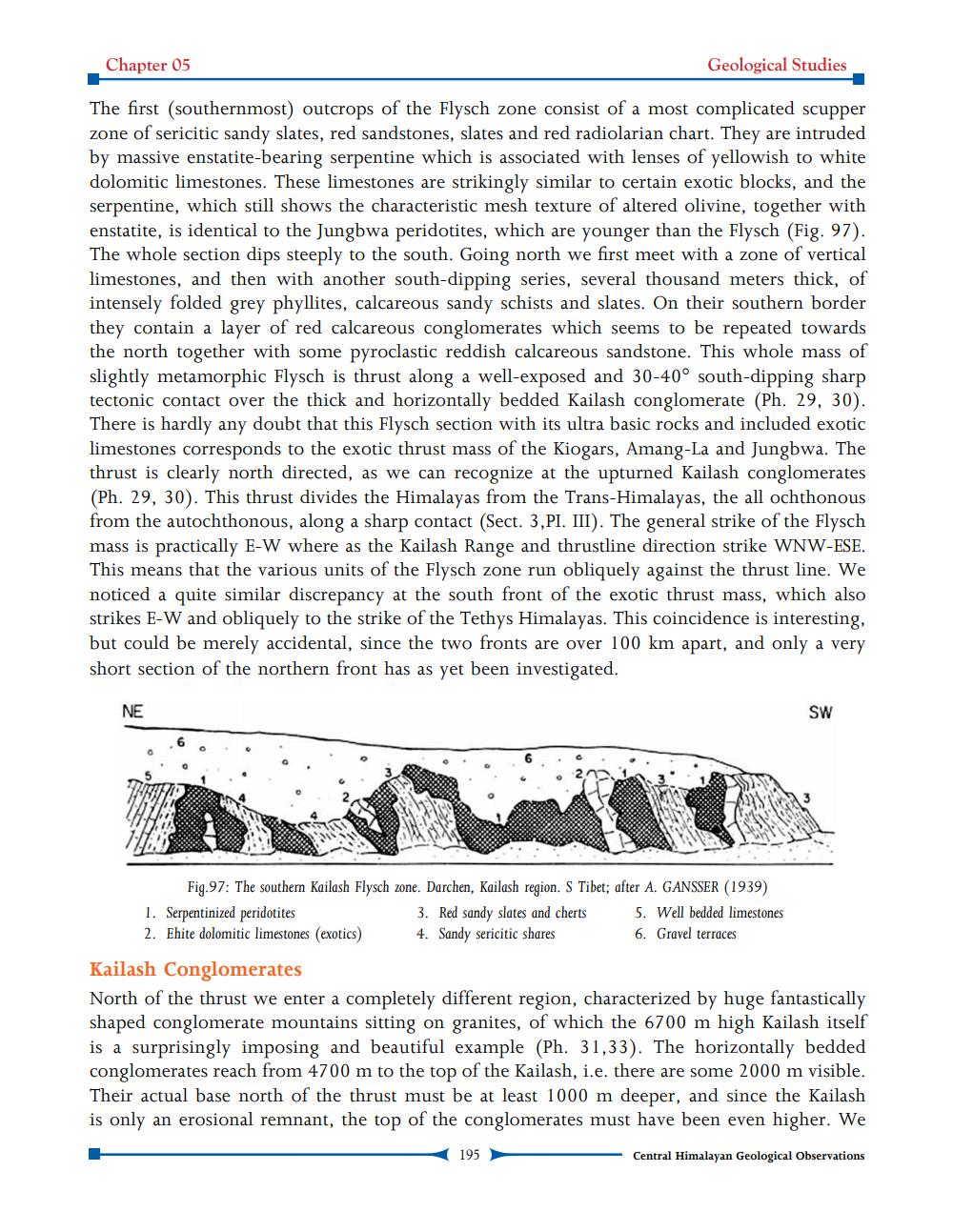

The first (southernmost) outcrops of the Flysch zone consist of a most complicated scupper zone of sericitic sandy slates, red sandstones, slates and red radiolarian chart. They are intruded by massive enstatite-bearing serpentine which is associated with lenses of yellowish to white dolomitic limestones. These limestones are strikingly similar to certain exotic blocks, and the serpentine, which still shows the characteristic mesh texture of altered olivine, together with enstatite, is identical to the Jungbwa peridotites, which are younger than the Flysch (Fig. 97). The whole section dips steeply to the south. Going north we first meet with a zone of vertical limestones, and then with another south-dipping series, several thousand meters thick, of intensely folded grey phyllites, calcareous sandy schists and slates. On their southern border they contain a layer of red calcareous conglomerates which seems to be repeated towards the north together with some pyroclastic reddish calcareous sandstone. This whole mass of slightly metamorphic Flysch is thrust along a well-exposed and 30-40° south-dipping sharp tectonic contact over the thick and horizontally bedded Kailash conglomerate (Ph. 29, 30). There is hardly any doubt that this Flysch section with its ultra basic rocks and included exotic limestones corresponds to the exotic thrust mass of the Kiogars, Amang-La and Jungbwa. The thrust is clearly north directed, as we can recognize at the upturned Kailash conglomerates (Ph. 29, 30). This thrust divides the Himalayas from the Trans-Himalayas, the all ochthonous from the autochthonous, along a sharp contact (Sect. 3,PI. III). The general strike of the Flysch mass is practically E-W where as the Kailash Range and thrustline direction strike WNW-ESE. This means that the various units of the Flysch zone run obliquely against the thrust line. We noticed a quite similar discrepancy at the south front of the exotic thrust mass, which also strikes E-W and obliquely to the strike of the Tethys Himalayas. This coincidence is interesting. but could be merely accidental, since the two fronts are over 100 km apart, and only a very short section of the northern front has as yet been investigated.

NE

Fig.97: The southern Kailash Flysch zone. Darchen, Kailash region. S Tibet; after A. GANSSER (1939) 1. Serpentinized peridotites

3. Red sandy slates and cherts 4. Sandy sericitic shares

5. Well bedded limestones 6. Gravel terraces

2. Ehite dolomitic limestones (exotics)

SW

Kailash Conglomerates North of the thrust we enter a completely different region, characterized by huge fantastically shaped conglomerate mountains sitting on granites, of which the 6700 m high Kailash itself is a surprisingly imposing and beautiful example (Ph. 31,33). The horizontally bedded conglomerates reach from 4700 m to the top of the Kailash, i.e. there are some 2000 m visible. Their actual base north of the thrust must be at least 1000 m deeper, and since the Kailash is only an erosional remnant, the top of the conglomerates must have been even higher. We

Central Himalayan Geological Observations

195