________________

IN THE BOMBAY CIRCLE.

The motive for another maxim is probably a sanitary one still in force in India :

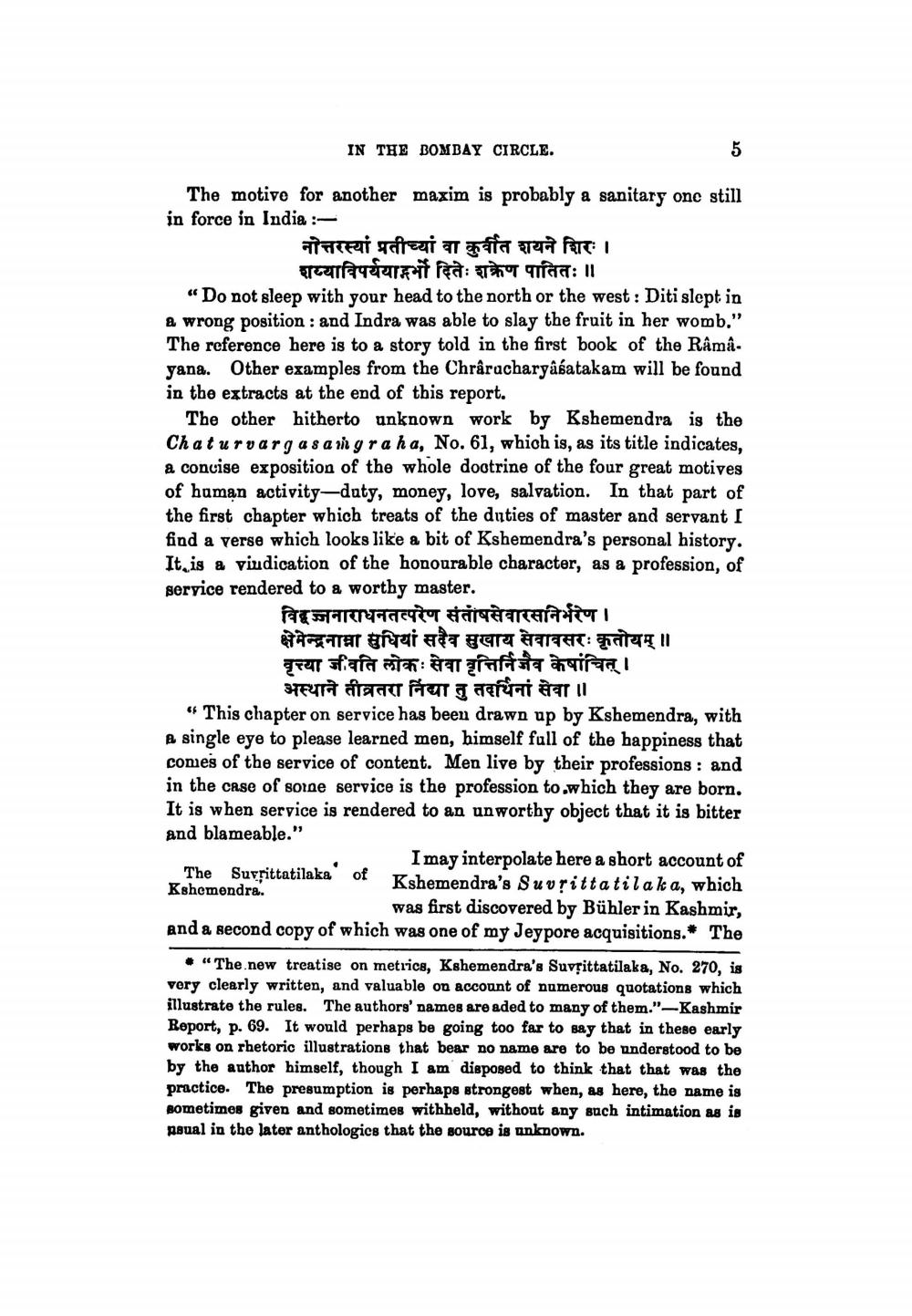

नोत्तरस्यां प्रतीच्यां वा कुर्वीत शयने शिरः । शय्याविपर्ययाद्गर्भो दितेः शक्रेण पातितः ॥

5

"Do not sleep with your head to the north or the west: Diti slept in a wrong position: and Indra was able to slay the fruit in her womb." The reference here is to a story told in the first book of the Râmâyana. Other examples from the Chrârucharyâśatakam will be found in the extracts at the end of this report.

The other hitherto unknown work by Kshemendra is the Chaturvargasam graha, No. 61, which is, as its title indicates, a concise exposition of the whole doctrine of the four great motives of human activity-duty, money, love, salvation. In that part of the first chapter which treats of the duties of master and servant I find a verse which looks like a bit of Kshemendra's personal history. It is a viudication of the honourable character, as a profession, of service rendered to a worthy master.

विद्वज्जनाराधनतत्परेण संतोषसेवारसनिर्भरेण ।

क्षेमेन्द्रनाम्ना सुधियां सदैव सुखाय सेवावसरः कृतोयम् ॥ वृत्त्या जीवति लोकः सेवा वृत्तिर्निजैव केषांचित् । अस्थाने तीव्रतरा निद्या तु तदर्थिनां सेवा ॥

"This chapter on service has been drawn up by Kshemendra, with a single eye to please learned men, himself full of the happiness that comes of the service of content. Men live by their professions: and in the case of some service is the profession to.which they are born. It is when service is rendered to an unworthy object that it is bitter and blameable."

I may interpolate here a short account of Kshemendra's Suvṛittatilaka, which was first discovered by Bühler in Kashmir, and a second copy of which was one of my Jeypore acquisitions. The

The Suvrittatilaka of Kshemendra.

"The new treatise on metrics, Kshemendra's Suvṛittatilaka, No. 270, is very clearly written, and valuable on account of numerous quotations which illustrate the rules. The authors' names are aded to many of them."-Kashmir Report, p. 69. It would perhaps be going too far to say that in these early works on rhetoric illustrations that bear no name are to be understood to be by the author himself, though I am disposed to think that that was the practice. The presumption is perhaps strongest when, as here, the name is sometimes given and sometimes withheld, without any such intimation as is nsual in the later anthologics that the source is unknown.