________________

FURTHER-INDIAN BRANCH

411 Anawrat'a or Anuruddha, who became king of Pagan about A.D. 1010, made Burma a kingdom and confirmed it in Buddhism. He invaded the Delta, and reduced a number of states, amongst them the Mons of Thaton and the Pyu of Prome, to vassalage.

The Burmans, having subdued the Mons, assimilated their culture and adopted their script. The script of the Buddhist monks of Thaton became therefore the main vehicle of the Mon-Burmese culture, based originally on an overflow from South India. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries A.D., the importation of Pali Buddhism from Ceylon was a reinforcement of Buddhist religion and culture.

It may be assumed that the Burmans adapted to their speech not only the Mon script, but also the script used for the Sinhalese Pali Buddhist canon. Indeed, the Burmese character contains only the Pali letters. There were thus two varieties of the ancient Burmese script: (1) The lapidary form (Fig. 154, col. 23), Kyok-cha or Kiusa, the "script (on) stone," made up of straight strokes meeting at right angles, was employed for the monumental inscriptions. (2) The more important "square" Pali script (Fig. 154, col. 24), a capricious, highly calligraphic character, was generally employed for writing the religious Buddhist books. This

။ ။ ကောင်းကင်ပယ် ခုတေသ၁န်ခံအဖ» ၁ည်တေ5 ။ ကိုယ်ဒခ၁ည်၁တေ၌ ရိုသေမြတ်နိုးသည်

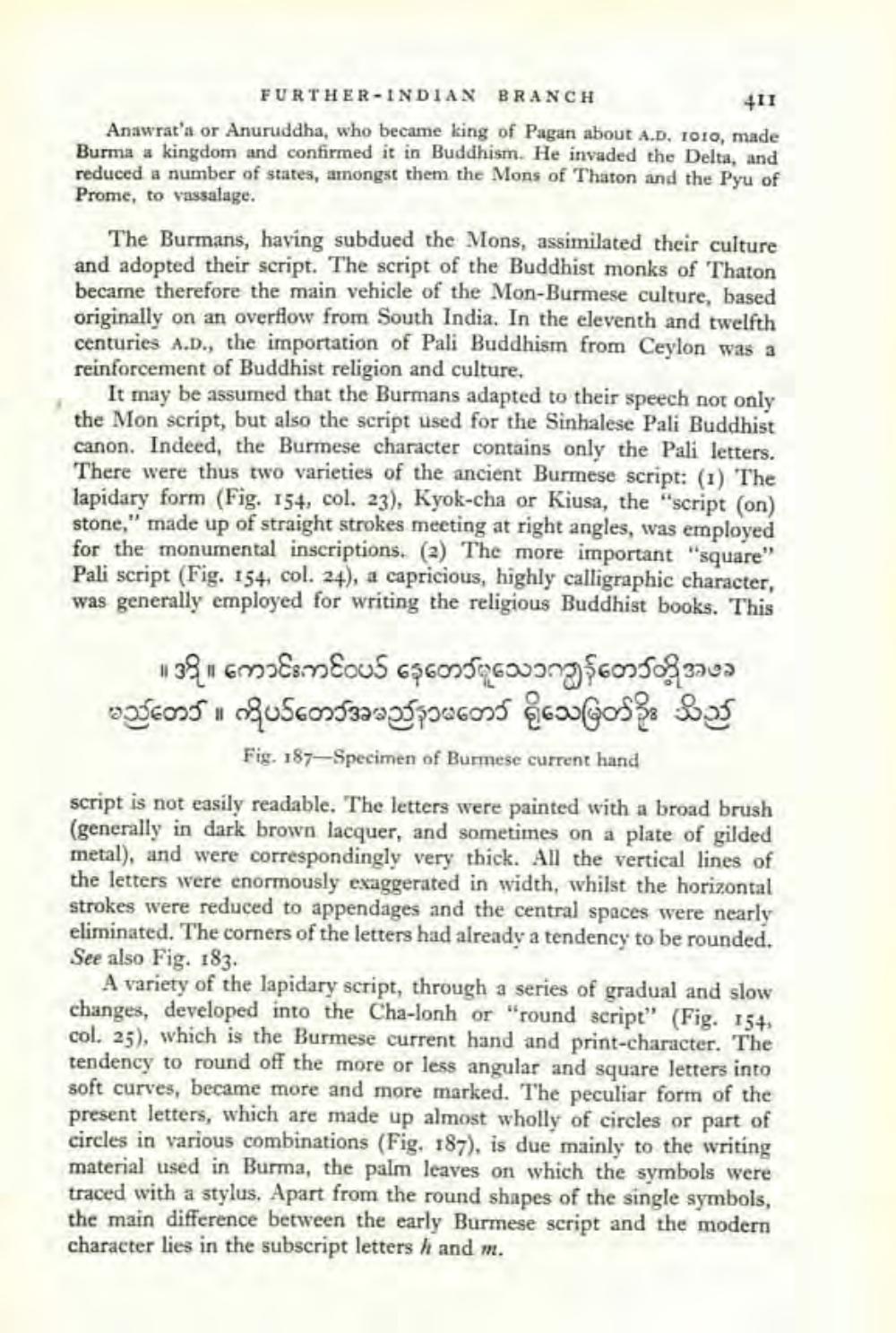

Fig. 187—Specimen of Burmese current hand script is not easily readable. The letters were painted with a broad brush (generally in dark brown lacquer, and sometimes on a plate of gilded metal), and were correspondingly very thick. All the vertical lines of the letters were enormously exaggerated in width, whilst the horizontal strokes were reduced to appendages and the central spaces were nearly eliminated. The corners of the letters had already a tendency to be rounded. See also Fig. 183.

A variety of the lapidary script, through a series of gradual and slow changes, developed into the Cha-lonh or "round script" (Fig. 15+, col. 25), which is the Burmese current hand and print-character. The tendency to round off the more or less angular and square letters into soft curves, became more and more marked. The peculiar form of the present letters, which are made up almost wholly of circles or part of circles in various combinations (Fig. 187), is due mainly to the writing material used in Burma, the palm leaves on which the symbols were traced with a stylus, Apart from the round shapes of the single symbols, the main difference between the early Burmese script and the modern character lies in the subscript letters h and m.