________________

FOREWORD

language devises its own methods and does not heed or tarry for the laws of purists. Sticklers may look askance or raise eye-brows but language, like the elephant in the procession, marches on unmindful of who follows or what happens behind. To the student of Sanskrit language, two things are noteworthy. First, it reflects the faith of the common people that what is written in Sanskrit will endure for centuries and even millennia. Second, that Sanskrit can cut across the rigidities of its grammar and don a popular garb when the occasion demands it. Such a development of hybrid Sanskrit can be of much consequence in the modern milieu.

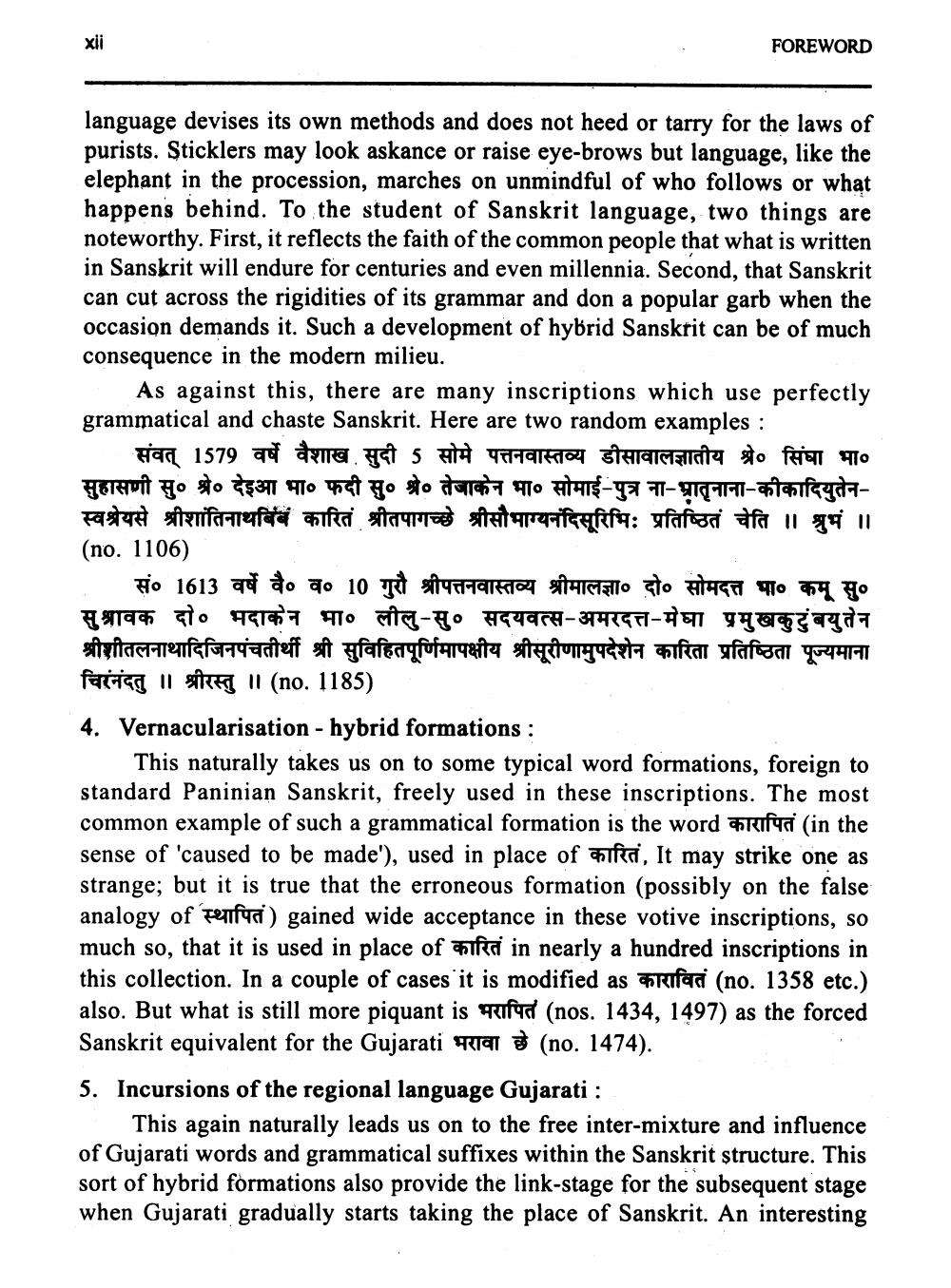

As against this, there are many inscriptions which use perfectly grammatical and chaste Sanskrit. Here are two random examples :

संवत् 1579 वर्षे वैशाख सुदी 5 सोमे पत्तनवास्तव्य डीसावालज्ञातीय श्रे० सिंघा भा० सुहासणी सु० श्रे० देइआ भा० फदी सु० अ० तेजाकेन भा० सोमाई-पुत्र ना-भ्रातृनाना-कीकादियुतेनस्वश्रेयसे श्रीशांतिनाथबिंब कारितं श्रीतपागच्छे श्रीसौभाग्यनंदिसूरिभिः प्रतिष्ठितं चेति ॥ श्रुभं ॥ (no. 1106)

RO 1613 ad do ao 10 met stalkia siteistilo sto #1467 90 74 70 सुश्रावक दो० भदाकेन भा० लीलु-सु० सदयवत्स-अमरदत्त-मेघा प्रमुखकुटुंबयुतेन श्रीशीतलनाथादिजिनपंचतीर्थी श्री सुविहितपूर्णिमापक्षीय श्रीसूरीणामुपदेशेन कारिता प्रतिष्ठिता पूज्यमाना facial li sterg II (no. 1185) 4. Vernacularisation - hybrid formations :

This naturally takes us on to some typical word formations, foreign to standard Paninian Sanskrit, freely used in these inscriptions. The most common example of such a grammatical formation is the word Rifua (in the sense of 'caused to be made'), used in place of whici, It may strike one as strange; but it is true that the erroneous formation (possibly on the false analogy of Fearfedi) gained wide acceptance in these votive inscriptions, so much so, that it is used in place of fa in nearly a hundred inscriptions in this collection. In a couple of cases it is modified as fritadi (no. 1358 etc.) also. But what is still more piquant is kifd (nos. 1434, 1497) as the forced Sanskrit equivalent for the Gujarati भरावा छे (no. 1474). 5. Incursions of the regional language Gujarati :

This again naturally leads us on to the free inter-mixture and influence of Gujarati words and grammatical suffixes within the Sanskrit structure. This sort of hybrid formations also provide the link-stage for the subsequent stage when Gujarati gradually starts taking the place of Sanskrit. An interesting