________________

DEATH AGAINST ONE'S WILL shows the dying monk lying on his outspread cloth, while the dying layman is attended this time by a monk.

It might be assumed that the death of the layman is that against one's will and that of the monk is according to one's will; but I am inclined to believe that both represent death according to one's will. The advisability for a layman to die in this latter way is stressed throughout the chapter, and it is very easy to explain the monk who attends the laymen in the DV painting (fig. 16) as the teacher whose presence is hinted in stanza 31 (see the translation given above).

6. THE FALSE ASCETIC This chapter teaches that ascetics, if they are to profit from their asceticism, must be followers of the Jain dogma. The manuscript illustrations concern a story which the commentaries attach to the first verse: "All men ignorant of the Truth are subject to pains; erring they suffer in many ways in the endless Samsāra." The tale is of a villager, who suffered acute and unmitigated misfortunes. Whatever he did, however hard he worked at his farming, he got no gain; and at last he left home. One night in a temple he saw a man with a beautifully decorated jar in his hand, who cleared and purified a spot, and then worshipped the vessel with sweets, flowers, food, and other offerings of the traditional Jain sort. After the worship, the man asked the pot for a mansion, which straightway appeared, and all night long the man enjoyed bathing, food, drink, and beautiful fullbreasted young women. In the morning he took the pot on his shoulder and went on his way. The astonished rustic followed, and started to serve this master of magic, and in due time won his favor. He then asked, as a boon, for happiness like that of the magician, and the latter gave him the Magic Art (vidya) and the pot. In elation the farmer returned to his village, and thinking, "Of what use is good fortune which is enjoyed with strangers, which is not enjoyed with one's friends, which no one else sees, not even one's enemies," he entertained all his friends through the grace of the wishing-pot and gave up plowing. One day, intoxicated with rum, he put the pot on his shoulder and started to dance, singing "How happy am I!” Just then he stumbled; the pot broke and fell; and the Magic Art escaped. He could never get the pot together again and reclaim the Magic Art, and without the Magic Art he returned to his life of poverty, becoming a servant, poor and miserable. So, says the story, are living beings made wretched when they are without the knowledge (vidya) of the Truth.

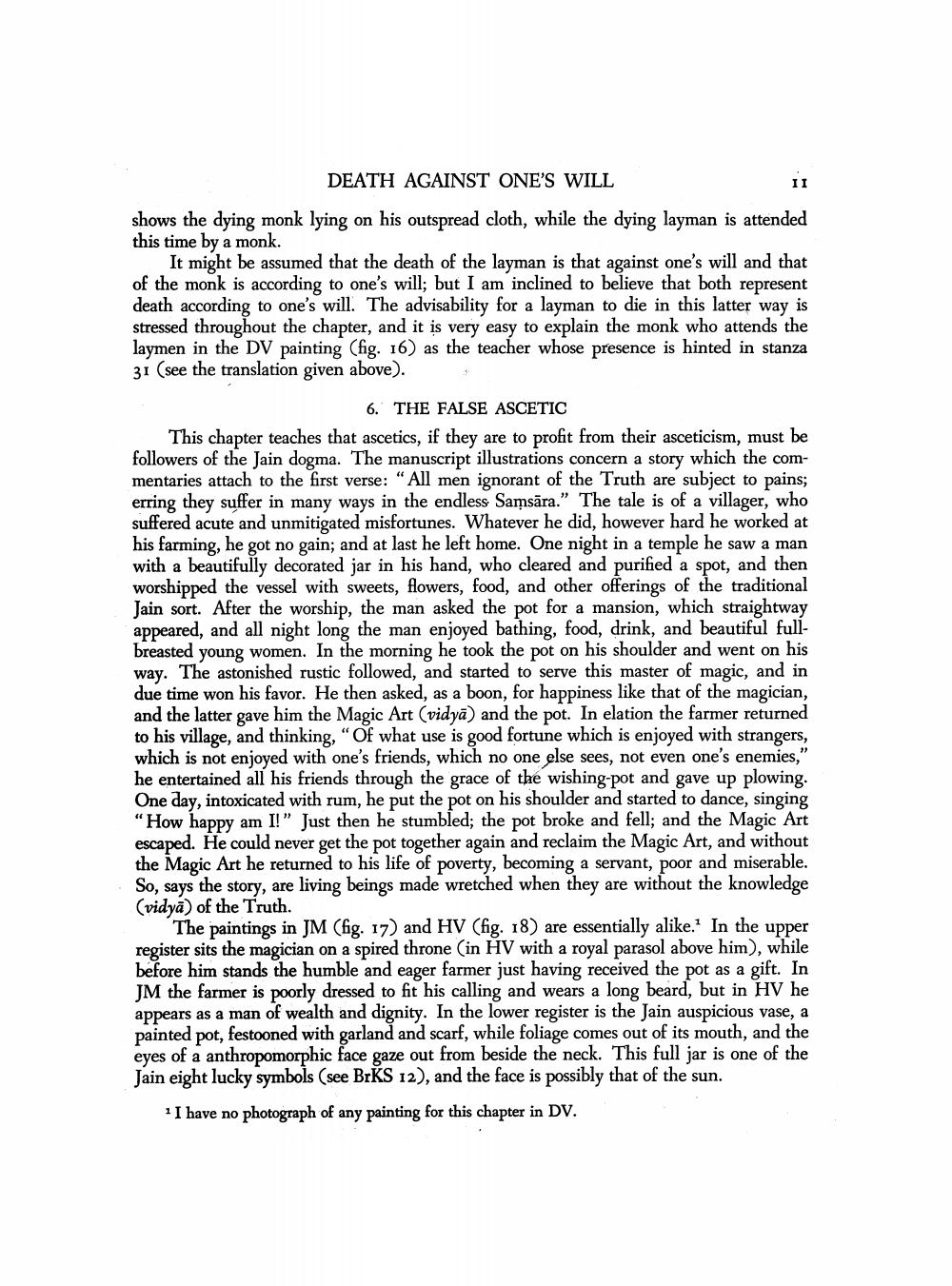

The paintings in JM (fig. 17) and HV (fig. 18) are essentially alike. In the upper register sits the magician on a spired throne (in HV with a royal parasol above him), while before him stands the humble and eager farmer just having received the pot as a gift. In JM the farmer is poorly dressed to fit his calling and wears a long beard, but in HV he appears as a man of wealth and dignity. In the lower register is the Jain auspicious vase, a painted pot, festooned with garland and scarf, while foliage comes out of its mouth, and the eyes of a anthropomorphic face gaze out from beside the neck. This full jar is one of the Jain eight lucky symbols (see BrŘS 12), and the face is possibly that of the sun.

I have no photograph of any painting for this chapter in DV.