________________

14

KUVALAYAMÂLÂ

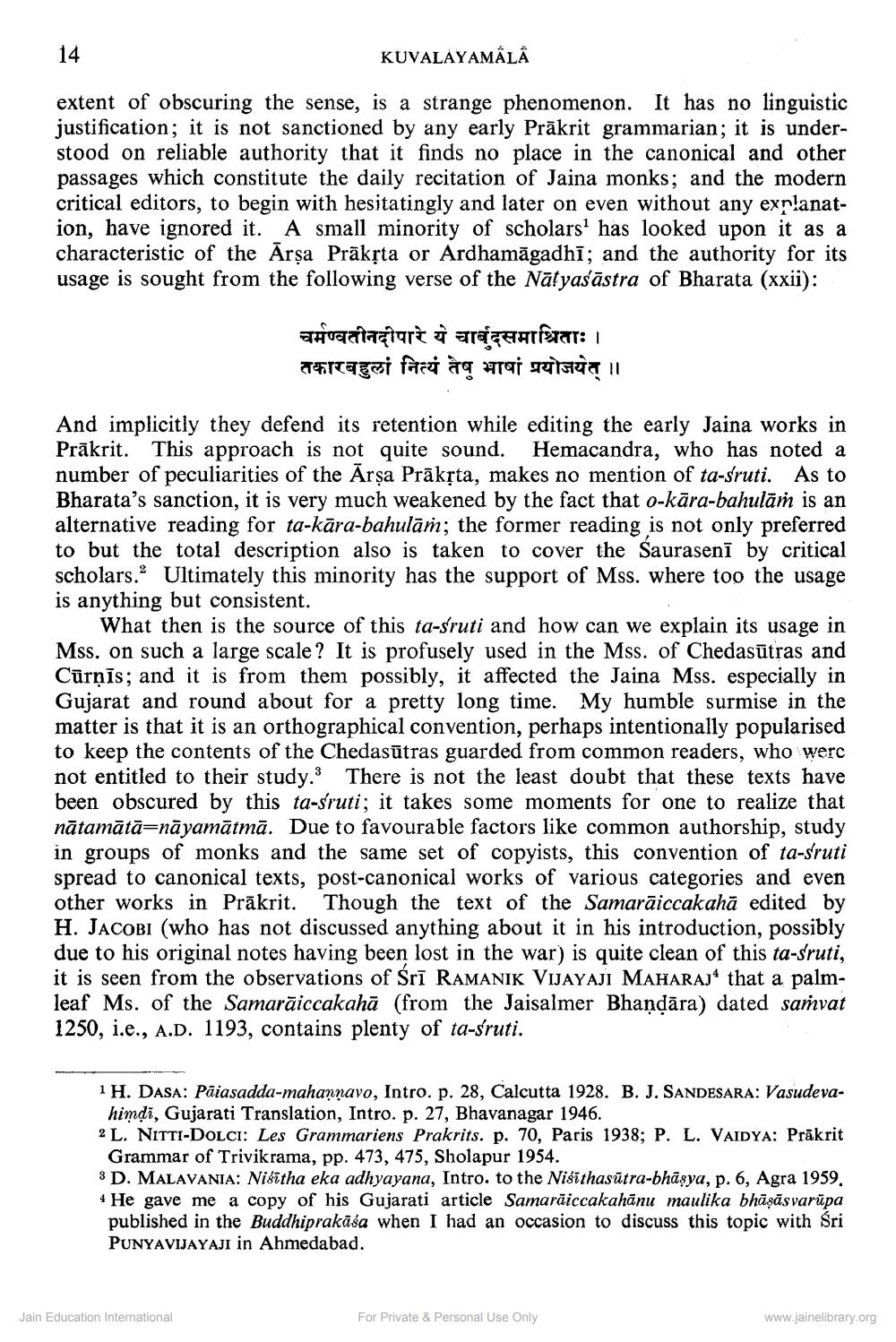

extent of obscuring the sense, is a strange phenomenon. It has no linguistic justification; it is not sanctioned by any early Prakrit grammarian; it is understood on reliable authority that it finds no place in the canonical and other passages which constitute the daily recitation of Jaina monks; and the modern critical editors, to begin with hesitatingly and later on even without any explanation, have ignored it. A small minority of scholars1 has looked upon it as a characteristic of the Arṣa Prakṛta or Ardhamāgadhī; and the authority for its usage is sought from the following verse of the Natyasastra of Bharata (xxii):

avaztagîurt & adzemfkran: 1 annagoi fazi àg moj goladą 11

And implicitly they defend its retention while editing the early Jaina works in Prakrit. This approach is not quite sound. Hemacandra, who has noted a number of peculiarities of the Arsa Prākṛta, makes no mention of ta-sruti. As to Bharata's sanction, it is very much weakened by the fact that o-kāra-bahulāṁ is an alternative reading for ta-kāra-bahulām; the former reading is not only preferred to but the total description also is taken to cover the Saurasenī by critical scholars.2 Ultimately this minority has the support of Mss. where too the usage is anything but consistent.

What then is the source of this ta-sruti and how can we explain its usage in Mss. on such a large scale? It is profusely used in the Mss. of Chedasūtras and Cūrṇīs; and it is from them possibly, it affected the Jaina Mss. especially in Gujarat and round about for a pretty long time. My humble surmise in the matter is that it is an orthographical convention, perhaps intentionally popularised to keep the contents of the Chedasūtras guarded from common readers, who were not entitled to their study. There is not the least doubt that these texts have been obscured by this ta-sruti; it takes some moments for one to realize that nātamātā=nāyamātmā. Due to favourable factors like common authorship, study in groups of monks and the same set of copyists, this convention of ta-sruti spread to canonical texts, post-canonical works of various categories and even other works in Prakrit. Though the text of the Samaraiccakahā edited by H. JACOBI (who has not discussed anything about it in his introduction, possibly due to his original notes having been lost in the war) is quite clean of this ta-sruti, it is seen from the observations of Śrī RAMANIK VIJAYAJI MAHARAJ1 that a palmleaf Ms. of the Samaraiccakaha (from the Jaisalmer Bhaṇḍāra) dated samvat 1250, i.e., A.D. 1193, contains plenty of ta-sruti.

1 H. DASA: Paiasadda-mahannavo, Intro. p. 28, Calcutta 1928. B. J. SANDESARA: Vasudevahimdi, Gujarati Translation, Intro. p. 27, Bhavanagar 1946.

2 L. NITTI-DOLCI: Les Grammariens Prakrits. p. 70, Paris 1938; P. L. VAIDYA: Prakrit Grammar of Trivikrama, pp. 473, 475, Sholapur 1954.

3 D. MALAVANIA: Nisitha eka adhyayana, Intro. to the Nisithasutra-bhāṣya, p. 6, Agra 1959. 4 He gave me a copy of his Gujarati article Samaraiccakahānu maulika bhāṣās varūpa published in the Buddhiprakasa when I had an occasion to discuss this topic with Sri PUNYAVIJAYAJI in Ahmedabad.

Jain Education International

For Private & Personal Use Only

www.jainelibrary.org