________________

INTRODUCTION

.

than 60° and 120° from the sun." The passage is not quite essential in the context and probably is an interpolation. Even if it is accepted as genuine it need not necessarily suggest & late date. For Tacobi's view about the period when the Hindus adopted Greek astrology is not incontestible. Dixit' holds that the Zodaic names Meşa and others were current in India round about five hundred years before the Saka or the Christian era and the names of week days about a thousand years before these eras started. Prof. Abhyankar believes in the identity of Minarāja or Minendra, the author of the Yavana Jātaka and King Menander (150 B. C.) and adds that the date of King Menander about 150 B. C.) also well agrees with the date which can be assigned to the work on strength of internal and external evidences."

The word 'Siyambara' (Svetimbara) used in the work appears not to have the Inter cannotation which it acquired after the great schism of the Jaina community into Svetārbaras and Digachbaras. In fact, the absence of the word Digambara in the whole of the work, the presence of beliefs and details of dogma which are in agreement with the Digambara tradition (and Ravişeņa's use of the work as the basis of bis Padmacharita or purāna) clearly suggest an early date for the work when scctarian prejudices bad not as yet developed.

There is striking resemblance between the Paūmachariya and the works of Kundakunda and Umāsvāti as pointed out by Pandit Paramanand Jajna. This kind of resemblance regarding doctrinal details, however, does not necessarily or invariably indicate the borrowing by one from the other but it

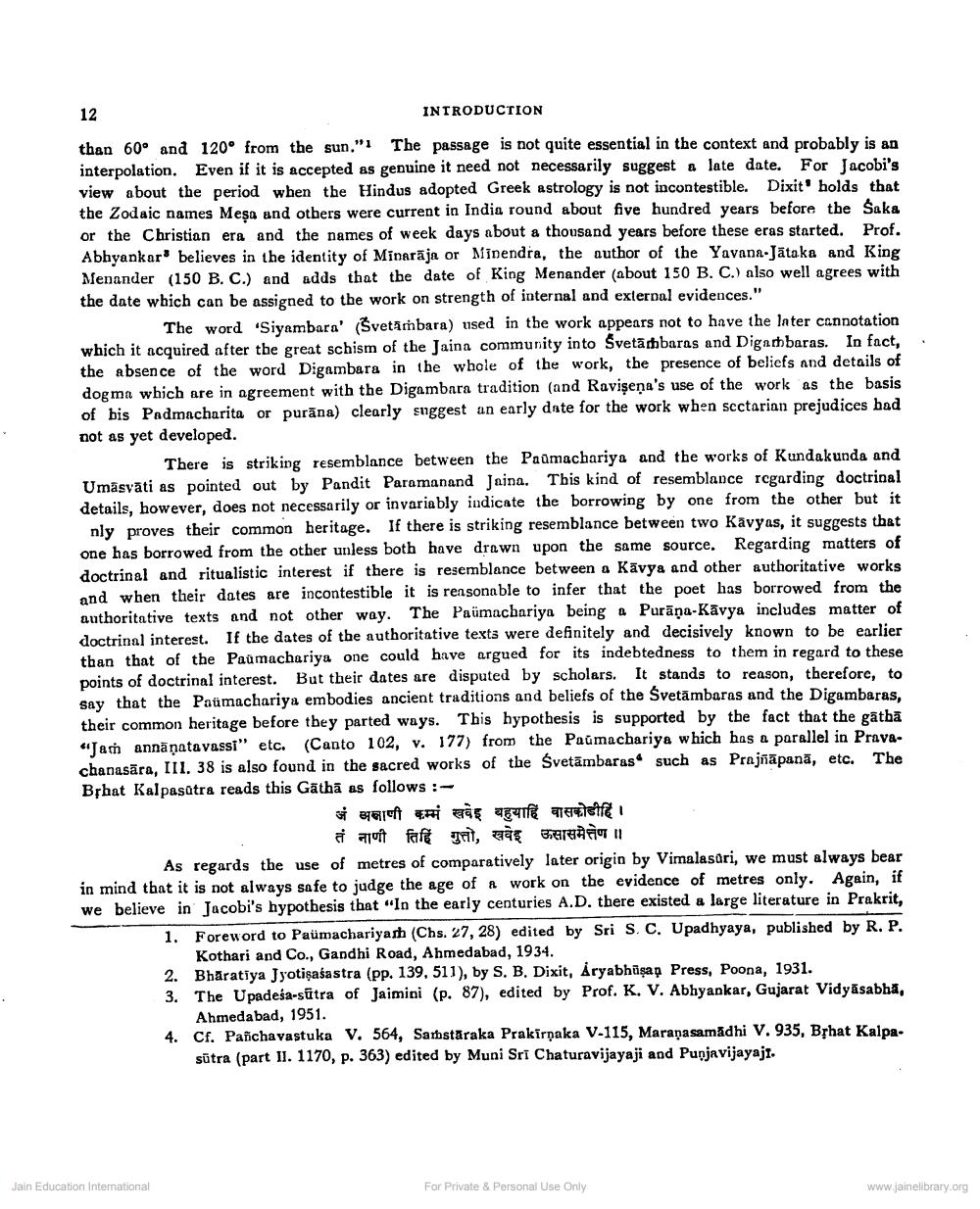

nly proves their common heritage. If there is striking resemblance between two Kavyas, it suggests that one has borrowed from the other unless both have drawn upon the same source. Regarding matters of doctrinal and ritualistic interest if there is resemblance between a Kāvya and other authoritative works and when their dates are incontestible it is rensonable to infer that the poet has borrowed from the authoritative texts and not other way. The Paümachariya being a Purana-Kavya includes matter of doctrinal interest. If the dates of the authoritative texts were definitely and decisively known to be earlier than that of the Paumachariya one could have argued for its indebtedness to them in regard to these points of doctrinal interest. But their dates are disputed by scholars. It stands to reason, therefore, to say that the Paumachariya embodies ancient traditions and beliefs of the Svetāmbaras and the Digambaras. their common heritage before they parted ways. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the gātba "Jam annāņatavassi" etc. (Canto 102, v. 177) from the Paumachariya which has a parallel in Pravachanasāra, III. 38 is also found in the sacred works of the Svetāmbaras such as Prajñāpanā, etc. The Brhat Kalpasūtra reads this Gatha as follows:

अं अनाणी कम्म खवेइ बहुयाहिं वासकोडीहिं ।

तं नाणी तिहिं गुत्तो, खवेइ ऊसासमेत्तेण ॥ As regards the use of metres of comparatively later origin by Vimalasari, we must always bear in mind that it is not always safe to judge the age of a work on the evidence of metres only. Again, if we believe in Jacobi's hypothesis that "In the early centuries A.D. there existed a large literature in Prakrit,

1. Foreword to Paumachariyash (Chs. 27, 28) edited by Sri S. C. Upadhyaya, published by R. P.

Kothari and Co., Gandhi Road, Ahmedabad, 1934. 2. Bharatiya Jyotişasastra (pp. 139, 511), by S. B. Dixit, Aryabhūşap Press, Poona, 1931. 3. The Upadeśa-sutra of Jaimini (p. 87), edited by Prof. K. V. Abhyankar, Gujarat Vidyāsabha,

Ahmedabad, 1951. 4. Cf. Pafchavastuka V, 564, Sarbstäraka Prakirņaka V.115, Maranasamadhi V. 935, Brhat Kalpa

sūtra (part II. 1170, p. 363) edited by Muni Sri Chaturavijayaji and Punjavijayaji.

Jain Education International

For Private & Personal Use Only

www.jainelibrary.org