________________

10

SOME PROBLEMS IN JAINA PSYCHOLOGY

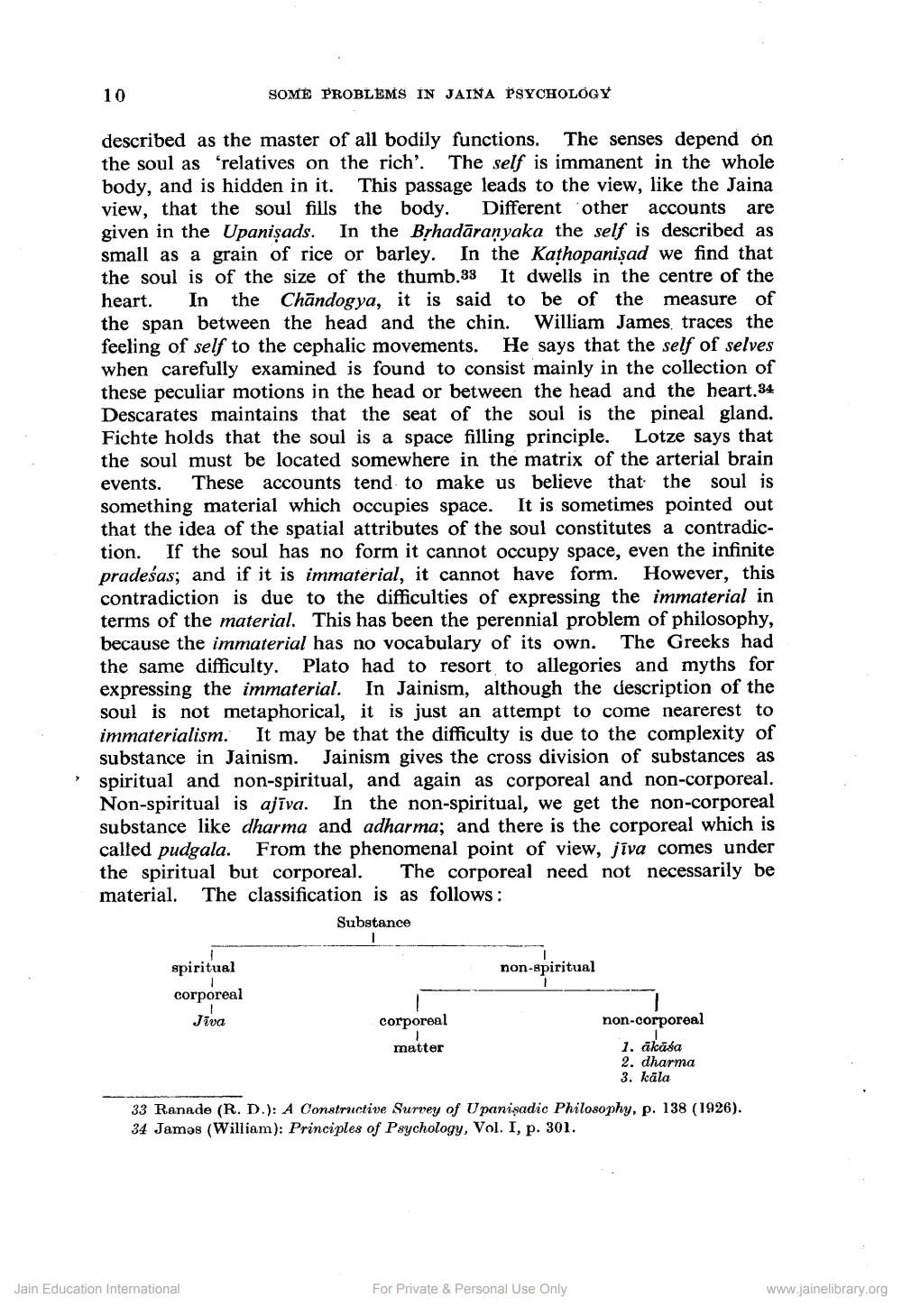

described as the master of all bodily functions. The senses depend on the soul as 'relatives on the rich'. The self is immanent in the whole body, and is hidden in it. This passage leads to the view, like the Jaina view, that the soul fills the body. Different other accounts are given in the Upanişads. In the Brhadāranyaka the self is described as small as a grain of rice or barley. In the Kathopanişad we find that the soul is of the size of the thumb.33 It dwells in the centre of the heart. In the Chāndogya, it is said to be of the measure of the span between the head and the chin. William James, traces the feeling of self to the cephalic movements. He says that the self of selves when carefully examined is found to consist mainly in the collection of these peculiar motions in the head or between the head and the heart.34 Descarates maintains that the seat of the soul is the pineal gland. Fichte holds that the soul is a space filling principle. Lotze says that the soul must be located somewhere in the matrix of the arterial brain events. These accounts tend to make us believe that the soul is something material which occupies space. It is sometimes pointed out that the idea of the spatial attributes of the soul constitutes a contradiction. If the soul has no form it cannot occupy space, even the infinite pradeśas; and if it is immaterial, it cannot have form. However, this contradiction is due to the difficulties of expressing the immaterial in terms of the material. This has been the perennial problem of philosophy, because the immaterial has no vocabulary of its own. The Greeks had the same difficulty. Plato had to resort to allegories and myths for expressing the immaterial. In Jainism, although the description of the soul is not metaphorical, it is just an attempt to come nearerest to immaterialism. It may be that the difficulty is due to the complexity of substance in Jainism. Jainism gives the cross division of substances as spiritual and non-spiritual, and again as corporeal and non-corporeal. Non-spiritual is ajīva. In the non-spiritual, we get the non-corporeal substance like dharma and adharma; and there is the corporeal which is called pudgala. From the phenomenal point of view, jīva comes under the spiritual but corporeal. The corporeal need not necessarily be material. The classification is as follows:

Substance

non-spiritual

spiritual corporeal

Jiva

corporeal

matter

non-corporeal

1. akāśa 2. dharma 3. kāla

33 Ranade (R. D.): A Constructive Survey of Upanisadic Philosophy, p. 138 (1926). 34 Jamos (William): Principles of Psychology, Vol. I, p. 301.

Jain Education International

For Private & Personal Use Only

www.jainelibrary.org