________________

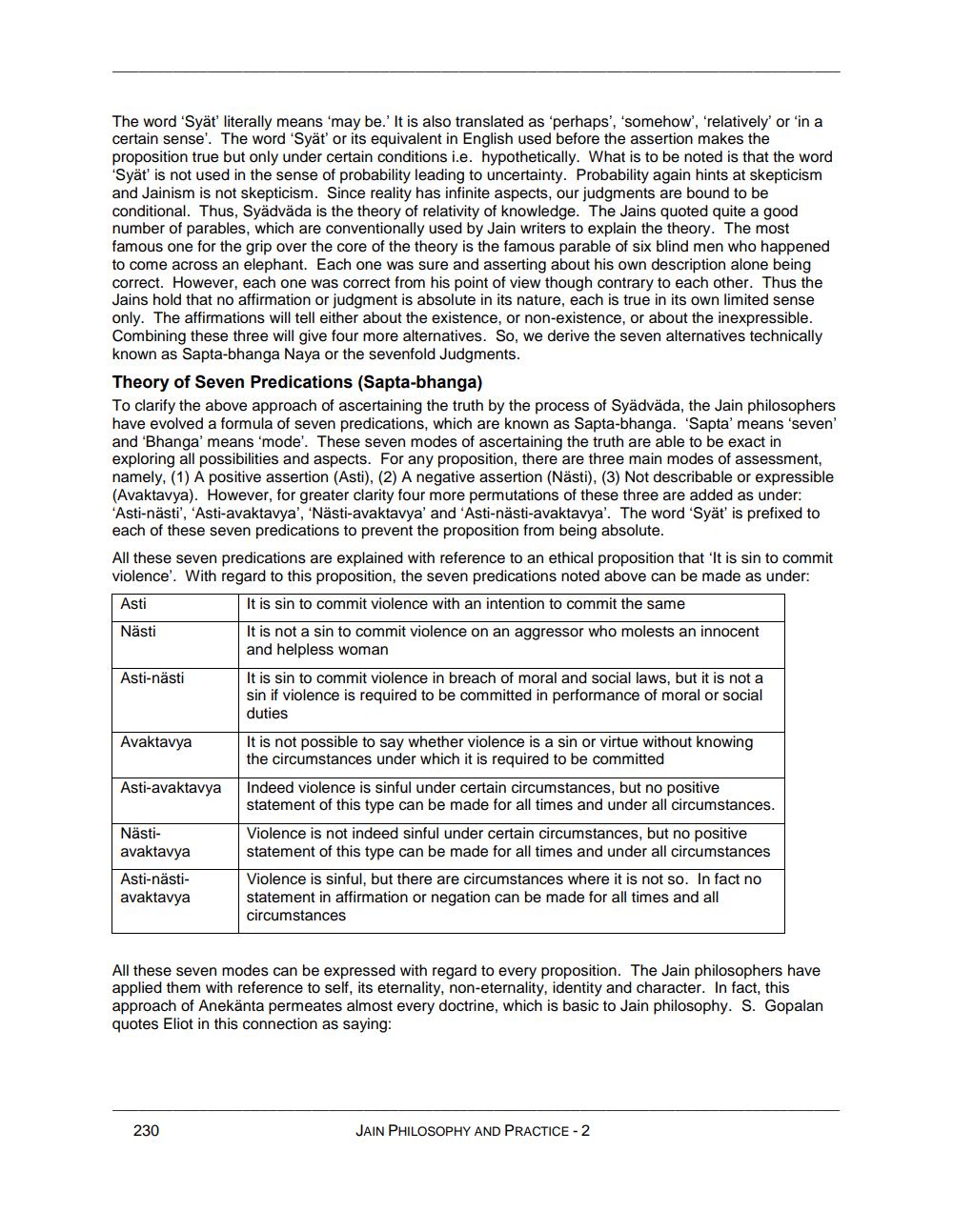

The word 'Syät literally means 'may be.' It is also translated as 'perhaps', 'somehow', 'relatively' or 'in a certain sense'. The word 'Syät' or its equivalent in English used before the assertion makes the proposition true but only under certain conditions i.e. hypothetically. What is to be noted is that the word 'Syät' is not used in the sense of probability leading to uncertainty. Probability again hints at skepticism and Jainism is not skepticism. Since reality has infinite aspects, our judgments are bound to be conditional. Thus, Syädväda is the theory of relativity of knowledge. The Jains quoted quite a good number of parables, which are conventionally used by Jain writers to explain the theory. The most famous one for the grip over the core of the theory is the famous parable of six blind men who happened to come across an elephant. Each one was sure and asserting about his own description alone being correct. However, each one was correct from his point of view though contrary to each other. Thus the Jains hold that no affirmation or judgment is absolute in its nature, each is true in its own limited sense only. The affirmations will tell either about the existence, or non-existence, or about the inexpressible. Combining these three will give four more alternatives. So, we derive the seven alternatives technically known as Sapta-bhanga Naya or the sevenfold Judgments. Theory of Seven Predications (Sapta-bhanga) To clarify the above approach of ascertaining the truth by the process of Syädväda, the Jain philosophers have evolved a formula of seven predications, which are known as Sapta-bhanga. 'Sapta' means 'seven' and 'Bhanga' means 'mode'. These seven modes of ascertaining the truth are able to be exact in exploring all possibilities and aspects. For any proposition, there are three main modes of assessment, namely, (1) A positive assertion (Asti), (2) A negative assertion (Nästi). (3) Not describable or expressible (Avaktavya). However, for greater clarity four more permutations of these three are added as under: 'Asti-nästi', 'Asti-avaktavya', 'Nästi-avaktavya' and 'Asti-nästi-avaktavya'. The word 'Syät' is prefixed to each of these seven predications to prevent the proposition from being absolute. All these seven predications are explained with reference to an ethical proposition that 'It is sin to commit violence'. With regard to this proposition, the seven predications noted above can be made as under: Asti

It is sin to commit violence with an intention to commit the same Nästi

It is not a sin to commit violence on an aggressor who molests an innocent and helpless woman

Asti-nästi

It is sin to commit violence in breach of moral and social laws, but it is not a sin if violence is required to be committed in performance of moral or social duties

Avaktavya

It is not possible to say whether violence is a sin or virtue without knowing the circumstances under which it is required to be committed

Asti-avaktavya

Indeed violence is sinful under certain circumstances, but no positive statement of this type can be made for all times and under all circumstances.

Nästiavaktavya

Violence is not indeed sinful under certain circumstances, but no positive statement of this type can be made for all times and under all circumstances

Asti-nästiavaktavya

Violence is sinful, but there are circumstances where it is not so. In fact no statement in affirmation or negation can be made for all times and all circumstances

All these seven modes can be expressed with regard to every proposition. The Jain philosophers have applied them with reference to self, its eternality, non-eternality, identity and character. In fact, this approach of Anekänta permeates almost every doctrine, which is basic to Jain philosophy. S. Gopalan quotes Eliot in this connection as saying:

230

JAIN PHILOSOPHY AND PRACTICE -2